BOLD: a technical deep dive

Overview

Under the hood, a reason why BOLD can offer time-bounded, permissionless validation is because a correct Arbitrum state assertion is not tied to a single validator or entity. Instead, claims are tied to deterministic Merkle proofs and hashes that will be proven on Ethereum. Any party can bond on the correct state and, through interactive fraud proofs, can prove their claim is correct. This means that a single honest party bonding on the correct state assertion will always win disputes, guaranteed.

To put it simply, Arbitrum’s current dispute protocol assumes that any assertion that gets challenged must be defended against by each unique challenger. It is similar to a 1-vs-1 tournament, where the honest party may participate in one or more concurrent tournaments at any time. BOLD, on the other hand, enables an all-vs-all battle royal between two categories: Good vs Evil, where there must and will always be a single winner in the end.

Validators on Arbitrum can post their claim on the validity of state roots, known as assertions. Ethereum, of course, does not know anything about the validity of these Arbitrum state roots, but it can help prove their correctness. Anyone in the world can then initiate a challenge over any unconfirmed assertion to start the protocol’s game.

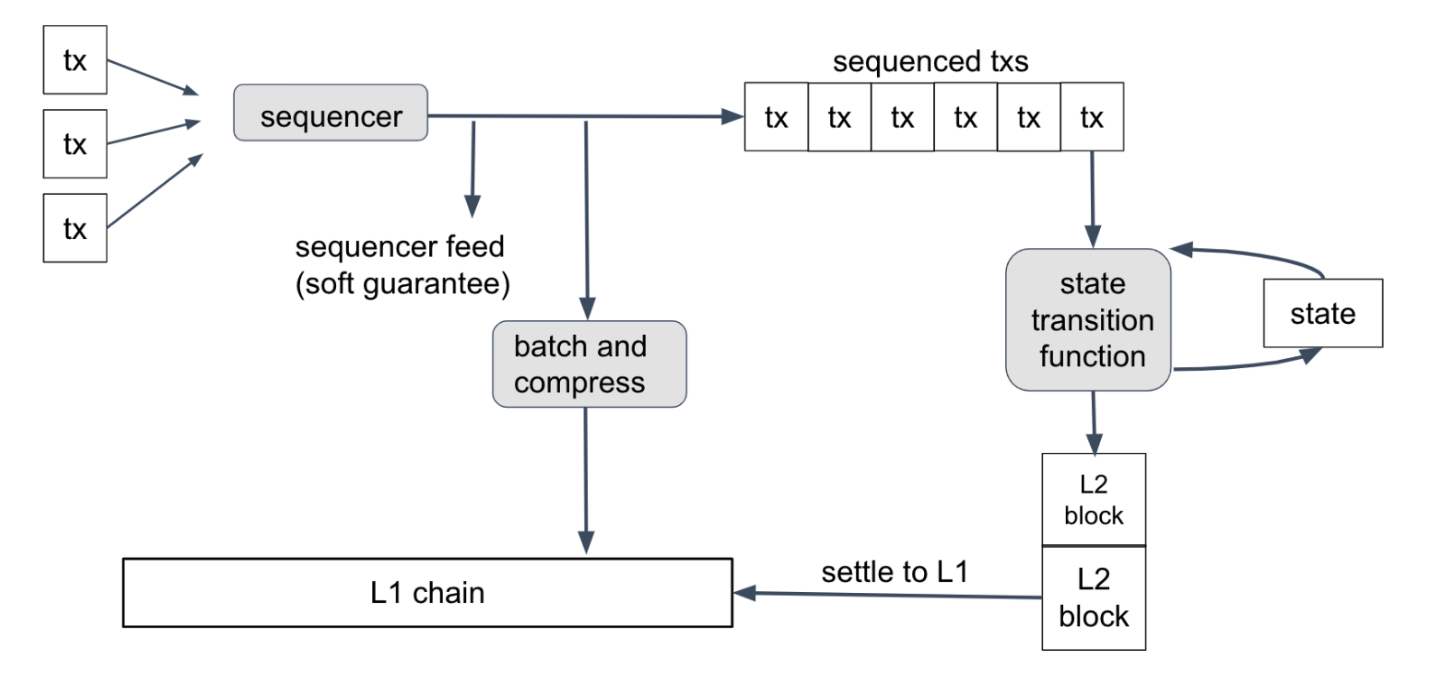

The assertions being disputed over are about block hashes of an Arbitrum chain at a given batch / inbox position. Given Arbitrum chains are deterministic, there is only one correct history for all parties running the standard Nitro software. Using the notion of a one-step-proof, Ethereum can check if someone is making a fraudulent assertion or not.

If a claim is honest, it can be confirmed on Ethereum after a 6.4 day period (although this period can be changed by the DAO). If a claim is malicious, anyone that knows the correct Arbitrum state can successfully challenge it within that 6.4 day window and always win within a challenge period.

The current implementation of BOLD involves both on-chain and off-chain components:

-

Rollup contracts to be deployed on Ethereum

-

New, challenge management contracts to be deployed on Ethereum

-

Honest validator software equipped to submit assertions and perform challenge moves on any assertions it disagrees with. The honest validator is robust enough to win against malicious entities and always ensure honest assertions are the only ones confirmed on-chain

Key terminology

-

Arbitrum Rollup Contracts: The set of smart contracts on Ethereum L1 that serve as both the data availability layer for Arbitrum and for confirming the rollup's state assertions after a challenge period has passed for each assertion made

-

Assertions: A claim posted to the Arbitrum rollup contracts on Ethereum L1 about the Arbitrum L2 execution state. Each claim consumes messages from the Arbitrum rollup inbox contract. Each assertion can be confirmed after a period of 6.4 days, and it can get challenged by anyone during that period. A BOLD challenge will add an additional upper bound of 6.4 days to the confirmation of an assertion. That is, if an assertion is challenged near the end of 6.4 days, an additional 6.4 days will be needed for the challenge to complete. Gaining the right to post assertions requires placing a large, one-time bond, which can get taken away in the case of losing a challenge to a competing assertion. Opening challenges requires opening smaller, “mini-bonds” each time.

-

Validating Bridge: The smart contract that leverages Ethereum's security and censorship-resistance to unlock bridged assets from L2 back to L1. Assets can be unlocked after an assertion has been posted and confirmed after a challenge period has passed

-

Fraud Proofs: Proofs of a single step of WAVM execution of Arbitrum's state transition function which are submitted to Ethereum and verified in the EVM via a smart contract. These proofs allow Ethereum to be the final arbiter of disagreements over assertions in the rollup contracts, which cannot be falsified by any parties as there is only a single, correct result of executing a WASM instruction on a pre-state.

-

Challenge Protocol: A set of rules through which a disagreement on an assertion is resolved using Ethereum as the final arbiter. Ethereum's VM can verify one step proofs of deterministic computation that can confirm a winner of a challenge in Arbitrum's rollup contracts.

-

Bonding of funds: Creating an assertion in the rollup contracts requires the submitter to join the validator set by putting up a large bond, in the form of WETH. Subsequent assertions posted by the same party do not require more bonds, instead, the protocol always considers validators to be bonded to their latest posted assertion. The bonded funds are taken away if another, competing assertion becomes confirmed. In the case of confirming an assertion, the associated bonded funds can be withdrawn

-

Honest Validator: An entity that knows the correct state of the Arbitrum L2 chain, and will participate in confirming assertions and challenging invalid assertions if they exist

-

Challenge Period: Window of time (~6.4 days on Arbitrum One) over which an assertion can be challenged, after which the assertion can be confirmed. This is configurable by the DAO.

-

Delay Attacks: In a delay attack, a malicious party (or group of parties) acts within the rollup protocol forcing the honest party to play 1-vs-1 games against them to delay the confirmation of results back to the L1 chain. BOLD has a proven, constant upper-bound on confirmation times for assertions in Arbitrum, addressing the biggest flaw of the current challenge mechanism. BOLD validators don’t need to play 1-vs-1 challenges, and instead can defend a single challenge against many malicious claims. With delay attacks solved, Arbitrum will be able to allow permissionless validation

-

Permissionless Validation: The ability for anyone to interact with the Arbitrum rollup contracts on Ethereum to both post assertions and challenge others' assertions without needing permission. With the release of BOLD, the rollup contracts on Arbitrum will no longer have a permissioned list of validators.

-

Validator Software: Software that has knowledge of the correct, Arbitrum L2 state at any point. It tracks the on-chain rollup contracts for assertions posted and will automatically initiate challenges on malicious assertions if configured to do so by the user. It will participate in new and existing challenges and make moves as required by the protocol to win against any number of malicious entities. Its goal is to ensure only honest assertions about Arbitrum's state are confirmed on Ethereum. All Arbitrum full nodes are watchtower validators by default. This means they do not post claims or assertions unless configured to do so, but will warn in case invalid assertions are detected onchain.

How BOLD Uses Ethereum

When it comes to implementing the protocol, BOLD needs to be deployed on a credibly-neutral, censorship-resistant backend to be fair to all participants. As such, Ethereum was chosen as the perfect candidate. Ethereum is currently the most decentralized, secure, smart contract blockchain where the full protocol can be deployed to, with challenge moves performed as transactions to the protocol’s smart contracts.

A helpful mental model to understand the system is that it uses Ethereum itself as the ultimate referee for deciding results of assertions. Participants in the challenge protocol can disagree over results of L2 state transitions, and they can provide proofs to the protocol smart contracts that show which result is correct. Because computation is deterministic, there will always be a single correct result.

From the Nitro whitepaper. L2 blocks are “settled to L1” after a 6.4 day period for each in which anyone can challenge their validity on Ethereum.

In effect, there is a miniature Arbitrum state-transition VM deployed as an Ethereum smart contract to prove which assertions are correct. However, computation on Ethereum is expensive, and this is why this mini-VM is built to handle “one-step proofs” which consist of a single step of WebAssembly code. The Arbitrum state transition logic, written in Golang, is also compiled to an assembly language called WASM and will therefore obtain the same results as the VM found in the on-chain smart contract. The soundness of the protocol depends on the assumptions that computation is deterministic and equivalent between the on-chain VM and the Golang state transition compiled to WASM .

All actors in the protocol have a local state of which they can produce valid proofs over, and all honest parties will have the same local state as each other. Malicious entities, however, can deviate from the honest parties in attempts to confirm invalid states through the protocol. Both the protocol and the honest validator client’s job is then to allow honest parties to always win against any number of malicious participants by always claiming the absolute truth

On-chain components

-

Rollup Contract: This is a smart contract that lives on Ethereum and allows validators to bond on state assertions about Arbitrum. This contract, known as

RollupCore.sol, is already used by Arbitrum chains to post assertions. BOLD requires several changes to how assertions work in this contract and it now contains a reference to another contract called a ChallengeManager, new in BOLD -

ChallengeManager: this is a contract that allows for initiating challenge on assertions within the

AssertionChainand provides methods for anyone to participate in challenges in a permissionless fashion. This new challenge protocol will require a newChallengeManagerwritten in Solidity and deployed to Ethereum. The challenge manager contains entrypoints for making challenge moves, opening leaves, creating subchallenges, and confirming challenges -

OneStepProver: A set of contracts that implement a miniature WASM VM capable of executing one-step-proofs of computation of the L2 state transition function. This is implemented in Solidity and already exists on Ethereum. No changes to the OSP contracts are needed for BOLD.

-

Bonding (also referred to as Staking): Participants in the protocol need to bond a certain amount of ETH (WETH is used in the BOLD testnet) to gain the privilege of posting assertions to the rollup contracts. by locking up an ETH bond in the protocol contracts. Whenever someone wants to challenge an assertion, they must also place a smaller bond called a mini-bond in their challenge. bonds, their rationale, and magnitude will be covered in greater detail in the Specifications section.

Off-chain components

-

Chain bindings: Software that can interact with an Ethereum node in order to make calls and transactions to the onchain contracts needed for participating in the protocol. We utilize go-ethereum’s abigen utilities to create Go bindings to interact with the contracts above, with a few more developer-friendly wrappers

-

State manager backend: Software that can retrieve L2 chain states and produce commitments to WAVM histories for Arbitrum based on an execution server. The validator client, described below, will have access to a state manager backend in order to make moves on challenge vertices.

-

Validator Client: A validator client is software that knows the correct history of the Arbitrum L2 chain, via a state manager backend, and can create assertions on L1 about them by bonding a claim. A validator is also active in ensuring honest assertions get confirmed and participate in challenging those it disagrees with. In BOLD, an honest validator will also participate in challenges other validators are a part of to support other honest participants. It interacts with the on-chain components via chain bindings described above.

-

Challenge Manager Client: Software that can manage the life cycles of challenges a validator is participating in. Validators need to participate in multiple challenges at once, and they need to manage individual challenge vertices correctly in order to act upon, confirm, or reject them. This and the validator responsibilities can be coupled into a single binary.

Assertions

A key responsibility for Arbitrum validators is to post claims about the Arbitrum chains’ state to Ethereum at certain checkpoints. These are known as assertions and they contain the following information, along with some metadata not critical for this document:

-

The L2 block hash being claimed

-

The batch number it corresponds to for the Arbitrum chain

-

The number of messages in the Arbitrum inbox at the time the assertion was posted onchain

The next assertion to be posted onchain must consume, at least, the specified number of inbox messages from its parent. There is a required delay, in L1 blocks, for assertion posting. Currently, this value is set to 1 hour for BOLD.

Assertions can be confirmed by anyone after a period of 6.4 days if they have not been challenged. In particular, assertions are used to facilitate the process of withdrawing from Arbitrum back to Ethereum. Arbitrum withdrawals require specifying a blockhash, which must be confirmed as an assertion onchain. This is why withdrawals have a delay of 6.4 days if they are not actively challenged.

To start posting assertions, a validator must become a bondr in the rollup contract. To do this, they must place a one-time bond of size N WETH that is locked in the contract until they choose to unbond. Validators can only unbond if their latest posted assertion has been confirmed. Each assertion a validator posts will become their latest bondd assertion. Subsequent bonds are not needed to post more assertions, instead, the protocol “moves” validators’ bonds to their latest posted assertion.

Assertions form a chain, in which there can be forks. For instance, a validator might disagree with the L2 blockhash of an assertion at a given batch. All Arbitrum Nitro nodes are configured to warn users if they observe an assertion they disagree with posted onchain. However, if a node is configured as a validator, it will have the responsibility to post the correct, rival assertion to any invalid one it just observed. The validator will also initiate a challenge by posting a mini-bond and some other data to the ChallengeManager, signaling it is disputing an assertion.

Overflow assertions

Given there is a mandatory delay of 1 hour between assertions posted onchain, and each assertion is a claim to a certain Arbitrum batch, there could be a very large number of blocks in between assertions. However, a single assertion only supports a maximum of 2^26 Arbitrum blocks since its parent. If this value is overflowed, a follow-up, overflow assertion needs to be posted to consume the rest of blocks above the maximum. This overflow assertion will not be subject to the mandatory 1 hour delay between assertions.

Trustles Bonding Pools

A large upfront assertion bond is critical for discouraging malicious actors from attacking Arbitrum and spamming the network (e.g. delay attacks) - especially when considering the fact that malicious actors will always lose challenges and their entire bond. On the other hand, requiring such a high upfront assertion bond may be prohibitively high for a single honest entity to put up - especially since the cost to defend Arbitrum is proportional to the number of malicious entities and on-going challenges at any given point in time.

To address this, there is a contract that anyone can use to deploy a trustless, bonding (or staking) pool as a way of crowdsourcing funds from others who wish to help defend Arbitrum, but who may otherwise not individually be able to put up the large upfront bond itself.

Anyone can deploy an assertion bonding pool using the AssertionStakingPoolCreator.sol contract as a means to crowdsource funds for bonding funds to an assertion. To defend Arbitrum using one of these pools, an entity would first deploy this pool with the assertion that they believe is correct and wish to bond on to challenge an adversary's assertion. Then, anyone can verify that the claimed assertion is correct by running the inputs through their node's State Transition Function (STF). If other parties agree on the assertion being correct, then they can deposit their funds into the contract. When enough funds have been deposited, anyone can trigger the creation of the assertion on-chain to start the challenge in a trustless manner. Finally, once the honest parties' assertion is confirmed by the dispute protocol, all involved entities will get their funds reimbursed and can withdraw.

Trustless bonding pools can also be created for opening challenges and making moves on challenges, without sacrificing decentralization.

Opening Challenges

To initiate a challenge, there must first be a fork in the assertion chain within the Arbitrum Rollup contracts. However, the actual start of a challenge involves creating a claim called an edge and posting it to the ChallengeManager contract on Ethereum. Additionally, the validator posting the edge must attach a bond called a mini-bond to it, denominated in WETH for the BOLD testnet. This bond is much lower than the one required to become an assertion poster.

Anyone can open a challenge on an assertion without needing to be a bondr in the rollup contract, so long as they post a mini-bond and an edge claiming intent to start the challenge. Challenges are not tied to specific addresses or parties – instead, anyone can participate.t

Recall that a challenge is about a fundamental disagreement about an assertion posted to the Arbitrum chain. At its core, validators disagree about the blockhash at a certain block number, essentially, and the BOLD protocol allows them to interactively narrow down their disagreement via cryptographic proofs such that Ethereum can be the final referee and claim a winner.

At its core, the disagreement between validators looks something like this:

Common parent assertion: batch 5, blockhash 0xabc

Alice’s assertion: batch 10, blockhash 0x123

Bob’s assertion: batch 10, blockhash 0x456

That is, their disagreement is about an Arbitrum block somewhere between batch 5 and batch 10. Here’s how the actual challenge begins in this example:

Validators have to fetch all blocks in between batch 5 and batch 10 and create a Merkle commitment out of them, as a Merkle tree with 2^26 leaves. If there are fewer than 2^26 blocks in between the assertions, the last block is repeated to pad the leaves of the tree to that value. Validators then create an “edge” data structure, which contains the following fields:

-

start_hash: the start hash of the block from the common parent assertion

-

**end_hash: **the end hash of the block at the claimed, child assertion

-

merkle_root: the Merkle root that results from committing to a Merkle tree from the start block hash to the end block hash

-

inclusion_proofs: Merkle proofs that the start and end hashes are indeed leaves of the Merkle tree committing to a root

At the core of challenges and BOLD itself is the concept of a history commitment.

The validators above provide a Merkle proof of their commitment to some history, in this case, all the Arbitrum block hashes from batch 5 to batch 10. Using this tree, validators can narrow down their disagreement to a single block using Merkle proofs.

Challenge resolution

The fundamental unit in a challenge is an edge data structure.

Initiation

The first validator to create an edge initiates a challenge. The smart contracts validate the Merkle inclusion proofs and hashes provided to prove this challenge is about a specific fork in the assertion chain in the rollup contract.

Bisections

When an edge is created, it claims some history from some point A to B in which validators can agree or disagree. Other validators can claim some history from point A to B’, where B’ is a different end state. A history commitment is a Merkle commitment to a list of hashes.

To narrow down a disagreement, validators have to figure out what exact hash they disagree with. To do this, the game essentially takes turns between validators playing binary search. Each move here is known as a “bisection”, because each move splits a history commitment in half.

For instance:

Alice commits to 32 hashes with start = A, end = B

Bob commits to 32 hashes with start = A, end = B’

Either of them can perform a “bisection” move on their edge. For instance, if Alice “bisects” her edge E, the bisection transaction will produce two children E_1 and E_2. E_1 commits to 16 hashes from height A to B/2 and E_2 commits to 16 hashes from height B/2 to B.

A validator can make a move on an edge as long as that edge is “rivaled”. That is, the children that were just created as a result of Alice’s bisection will have increasing timers until Bob also bisects and possibly creates rivals for Alice’s edges.

Subchallenges

The number of steps of execution at which validators could disagree within a single Arbitrum block has a max of 2^43. To play a game of bisections on this amount of hashes would be unreasonable from a space requirement, as each history commitment would require 8.7Tb worth of hashes. Instead, BOLD plays the bisection game over different levels of granularity of this space of 2^43 hashes.

First, validators disagree over Arbitrum blocks in between two assertions. They make “edges” containing history commitments to all the blocks in between those two assertions, and play the bisection game. Once they narrow down to a single block of disagreement, they now need to find where they disagree in the actual WASM execution of the block through the Arbitrum state transition function. This is what we call the first “subchallenge”.

The subchallenge is over a max of 2^43 hashes where validators need to narrow down their single hash of disagreement. As the space of hashes is too large, we explore this space in ranges of steps.

First, validators disagree over Gigasteps of WASM execution. That is, over ranges of 2^30 steps. Then, they open another subchallenge once they reach a single gigastep of disagreement. They then play games over ranges of Megasteps, then Kilosteps, until they reach a subchallenge over individual steps. The bisection game is the same at each subchallenge level, and opening a subchallenge requires placing another “mini-bond”. The magnitudes of mini-bonds are different at each subchallenge level.

One step proof

Once validators reach a single, individual step of disagreement after reaching the deepest subchallenge level, they then need to provide something called a one step proof, or OSP for short. This is a proof of WASM execution showing that executing the Arbitrum state transition function at hash A leads to hash B. Ethereum then actually runs a WASM emulator using a smart contract for this step, and will declare a winner. An evil party cannot forge a one-step-proof, and unless there is a critical bug in the smart contract, the honest party will always win. At this point, the honest party’s one step proven edge will be confirmed and the evil party has no more moves to make. Next, the honest party’s “branch” of edges all the way from the top to the one step proven edge will have an ever increasing timer until the top edge can be confirmed by time.

Timers

Once a validator creates an edge, and if it does not have any rival edge contesting it, that edge will have a timer that ticks up called its unrivaled timer. Time in the protocol is measured in L1 blocks, and block numbers are used. An edge’s timer stops ticking the moment it has a rival edge created onchain.

Edges also have something called an inherited timer, which is the sum of its unrivaled timer + the minimum inherited timer of an edge’s children (recursive definition). Once one of the top-level edges that initiated a challenge has achieved an inherited timer >= a CHALLENGE_PERIOD (6.4 days), it can be confirmed. At this point, the assertion it claims can also be confirmed as its associated challenge has completed. A minor, but important detail is that edges also inherit the time their claimed assertion was unrivaled.

We believe timer inheritance from ancestor edges is fundamentally broken, as honest edges could have evil ancestors, or vice-versa and edges could steal / claim timer credit from others they should not be entitled to. The research specification goes in-depth into proven lemmas of timer inheritance and why children inheritance solves critical attack vectors.

Cached timer updates

The “inherited timer” value of an edge exists onchain and can be updated via a transaction. Given it is a recursive definition, it can be updated via multiple transactions. First, the lowermost edges have their timers updated, then, their parents, etc. up to the top. Validators can track information locally to avoid sending wasteful transactions and only propagate updates once they are confident their edge is confirmable by time.

Confirmation

Once an edge has a total, onchain timer greater than or equal to a challenge period, it can be confirmed via a transaction. Not all edges need to be confirmed onchain, as simply the top-level, block challenge edge is enough to then confirm the claimed assertion and resolve a dispute. A challenge is not complete at the one step proof. It is only complete once the claimed assertion of a challenge is confirmed.

Bonding in Challenges

In order to create a challenge, there must be a fork in the Arbitrum assertion chain smart contract. A validator that wishes to initiate a challenge must then post an “edge” claiming a history of block hashes from the parent assertion to the claimed assertion they believe is correct, and to do so, they need to put up some value called a “mini-bond”.

Mini-bonds are named as such because they are a lot smaller than the base bond required to become an assertion poster, but still large enough such that they discourage spam attacks. The full mechanism of how mini-bond economics are decided are contained in the economics deep dive in this directory, which also explains the cost profile and spam prevention in BOLD. In short, the actual cost of a bond encompasses information such as offchain costs + gas costs + griefing ratios between honest and evil parties to discourage spam.

Each subchallenge that is created requires placing a “mini-bond”. The first, unrivaled edge’s bond is kept in the challenge manager contract on Ethereum, while any subsequent rival bonds are kept in an excess bond receiver address, which can be set to the DAO treasury. Once a challenge is complete, a reimbursement process can be done for honest party bonds, while the DAO keeps evil bonds. It is important to not offer evil bonds to honest parties to prevent perverse incentives such as griefing attacks or to discourage needless competition between honest parties.

Reimbursements of Bonds

It is important to emphasize that the reimbursement of assertion bonds for honest parties will be handled “in-band” by the protocol itself. While reimbursing honest parties for mini-bond costs and gas costs will not be handled “in-band” on L1 and will instead be handled by the Arbitrum DAO. There will be a procedure, published at a later date, that can be followed to calculate the reimbursements to be made for mini-bond and gas costs to honest parties.

Lastly, reimbursement will not be made for off-chain compute costs as we view these to be costs borne by the operator, alongside the maintenance and infra costs that regularly arise from running a node. It is also difficult to attribute computation, as honest validators that are not necessarily posting claims would still be performing similar computations if they are following a challenge. However, the costs of the on-chain bonds to participate in challenges far exceed the cost of compute required to resolve these challenges.

Upgrade Mechanism

For BOLD to be deployed on Arbitrum One and Nova, an upgrade admin action needs to be taken using an UpgradeExecutor pattern. This is a smart contract that executes actions as the rollup owner. At the upgrade, the RollupCore.sol contract will be updated to a new BOLD one, and additional contracts needed for BOLD challenges will also be deployed such as an EdgeChallengeManager.sol.

Assertions will then be posted to the new rollup contract. It is possible that during the upgrade period, there could have been a very large number of blocks posted in Arbitrum batches. For this purpose, BOLD assertions support the concept of an overflow, allowing us to handle this situation with ease.

The upgrade pattern for an existing Arbitrum rollup to a BOLD-enabled one is tested extensively and run as part of each of our pull requests in the BOLD repository here.